Mastering The Linux Shell : Making Things Disappear

Information begets information and eventually, there’s just too much of it. I don’t really believe that — I’m an information junkie — but there’s no question that if you never delete anything, eventually, you will either use up all your disk space, or you’ll have a terrible mess on your hands. Deleting and renaming files and directories is usually pretty simple stuff, but things can get weird and sometimes, simple is dangerous. Let’s start with the basics.

To delete a file, use the rm command.

rm file_name

Deleting a directory uses a similar command, rmdir.

rmdir directory_name

So far so good, but if you try to delete a directory using the rm command, you’lll get a message like this.

rm: cannot remove `fish': Is a directory

The fix is easy. Use the rmdir command instead. Unfortunately, things don’t always work the way you expect.

Strange Filenames That Just Won’t Go Away

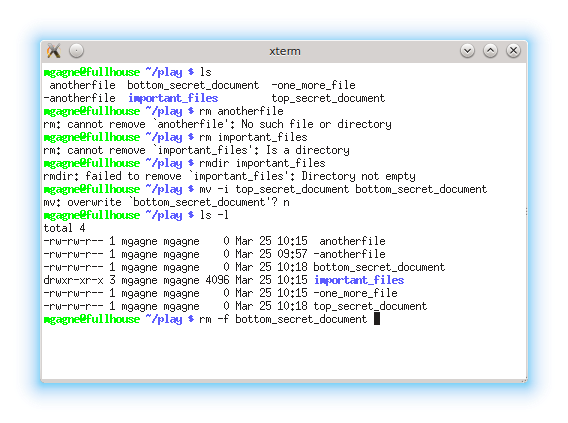

Every once in a while, you will do a listing of your directory and some strange file will appear that you just know isn’t supposed to be there. Don’t panic. It’s not necessarily a cracker at work. You may have mistyped something and you just need to get rid of it. The problem is that you can’t. Case in point: I accidentally created a couple of files with hard-to-deal-with names. I don’t want them there, but trying to delete them does not work. Here are the files:

-another_file onemorefile

Here’s what happens when I try to delete them:

$ rm -another_file rm: invalid option -- 'a' Try `rm --help' for more information.

What about that other file?

rm onemorefile rm: cannot remove `onemorefile': No such file or directory

The problem with the first file is that the hyphen makes it look like I am passing an option to the rm command. To get around this problem, I’ll use the double-dash option on the rm command. Using two dashes tells the command that what follows is not an option to that command. Here I go again:

rm -- -another_file

Bravo! By the way, this double-dash syntax applies to many other commands that need to recognize potentially weird filenames. Some Linux versions might actually help you out by telling you how to get around the issue using another method, specifying the full local path of the file.

rm ./-anotherfile

The dot is your current directory and the forward slash essentially says, “one down from the current directory”. In that way, the hyphen isn’t being passed as an option to the command. Now, what about the second file? It looked fine, didn’t it? If you look very closely, you’ll see that there is a space in front of the leading o, so simply telling rm to remove the file doesn’t work either, because “onemorefile” is not the filename. It is actually ” onemorefile”. So, I need to pass that space as well, and to do that I give the full name (space included) by enclosing the filename in double quotes.

rm " someotherfile"

Oops! I didn’t really mean that.

When you delete a file with Linux, it is gone. If you didn’t really mean to delete (or rm) a file, it is time to find out if you have been keeping good backups. The other option is to check with the rm command before you delete a file. Rather than simply typing rm followed by the filename, try this instead:

rm -i file_name1 file_name2 file_name3

The -i option tells rm to work in interactive mode. For each of the three files in the example, rm will pause and ask if you really mean it.

rm : remove 'file_name1'?

If you like to be a bit more wordy than that, you can also try

rm –interactive file_name, but that doesn’t really make things any easier.

Of course, in following that principle, you could remove all the files starting with the word file by using the asterisk.

rm –i file*

But beware the asterisk! It means “everything” and everything can be a dangerous thing to delete. Once you delete everything, you might want to leave the country or change your name.

Living Under An Alias

Okay, that suggestion sounds a bit drastic. You might find it safer to simply use the -i option every time you delete anything, just in case. It’s a lot easier to type Y in confirmation than it is to go looking through your backups. The problem is that you are adding keystrokes and everyone knows that system administrators are notoriously lazy people. Then there’s that whole issue of the first principle (lazy is good). That’s why we shortened “list” to simply ls, after all. Don’t despair, though, Linux has a way. It is the alias command.

alias rm='rm –i'

Now every time you execute the rm command, it will check with you beforehand. This behavior will only be in effect until you log out. If you want this to be the default behavior for rm, you should add the alias command to your local .bashrc file. If you want this to be the behavior for every user on your system, you should add your alias definitions to the system-wide version of this file, /etc/bash.bashrc, and save yourself even more time. Depending on your distribution, there may already be alias definitions set up for you. The first way to find out what has been set up for you is to type the alias command on a blank line at the command prompt.

$ alias alias cp='cp -i' alias ls='ls --color' alias mv='mv -i' alias rm='rm -i'

Depending on your distribution, or what user you are logged in as, that list may look quite different. Using the cat command, you can look in your local .bashrc file, or that system-wide /etc/bash.bashrc file and discover the same information. Remember that this can vary from system to system and user to user.

# cat .bashrc . . . lots of stuff might be in here, followed by, somewhere along the way, the following . . . # User specific aliases and functions alias rm='rm -i' alias cp='cp -i' alias mv='mv -i'

Well, isn’t this interesting? Notice the two other commands here, the cp (copy files) and mv (rename files) commands, and both have the -i flag as well. They too can be set to work interactively, verifying with you before you overwrite something important. Let’s say that I want to make a backup copy of a file called important_info using the cp command.

cp important_info important_info.backup

Perhaps what I am actually trying to do is rename the file (rather than copy it). For this, I would use the mv command. Move is the same as rename; take my word for it.

mv important_info not_so_important_info

The only time you would be bothered by an “Are you sure?” type of message is if the file already existed. In that case, you would get a message like the following:

mv: overwrite 'not_so_important_info'?

Forcing the Issue

The answer to the inevitable next question of “What do you do if you are copying, moving, or removing multiple files and you don’t want to be bothered with being asked each time when you’ve aliased everything to be interactive?” is this: Use the -f flag, which, as you might have surmised, stands for “force.” Once again, this is a flag that is quite common with many Linux command, either a -f or a –force.

Imagine a hypothetical scenario in which you move a group of log files daily so that you always have the previous day’s files as backup (but just for one day). If your mv command is aliased interactively, you can get around it like this:

mv –f *.logs /path_to/backup_directory/

Yes, yes, I know that mv looks more like move than rename. In fact, you do move directories and files using the mv command. Think of the file as a vessel for your data. When you rename a file with mv, you are moving the data into a new container for the same data, so it isn’t strictly a rename; you really are moving files. Looking at it that way, it doesn’t seem so strange. Sort of.

And finally, the reverse of the alias command is unalias. If you want your mv command to return to its original functionality, use this command:

unalias mv

Next time around, we’ll explore some under-appreciated but wickedly important files. You basic standard in and out action. Oh, please, get your mind out of the gutter. We’re talking command line Linux here. Sure it’s sexy, but not like that.

And that is where I will leave this discussion for today. Leave any comments you may have here on Google Plus or over here on Facebook. Join me this coming Thursday for part four in this series. Remember that you can also follow the action on CookingWithLinux.com where it’s all Linux, all the time. Except for the occasional wine review.

A votre santé! Bon appétit!

In case you missed it, you can find part one here and part two over here.