Mastering The Linux Shell – Finding Anything

If you like what I’m doing here, consider supporting my work on Patreon. Now, on with today’s post.

You know how you get those emails that suggest you can find out anything about anyone? They claim to be able to locate any person and tell you who they are, where they are from, the date they were born, and what their background is . . . You’ll be happy to know this isn’t the subject of this article. It’s a lot more fun than that. We’re going to find out where files are hiding and once we do, I’ll tell you what you can do with them. Sounds like fun? Then let’s get started.

Finding out about a specific file is as simple as using the file command. Let’s say you’ve got a file call secret_story in your directory. You try looking at file with the ‘cat‘ command but all you see is junk.

$ cat secret_story ���� ▒"#&)+.1458;=@CEGJMORUWY\_adghknqsvxz}������������������������������������������� ������ �]���9��M4B�CCA��^Ld�u!оu���z���:�H�_��on4

What could it be? A strange program meant to destabilize our democracy? Something even worse? Let’s use the file command and find out.

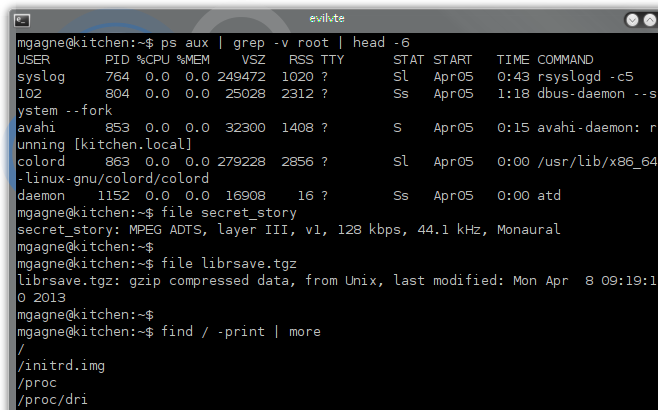

$ file secret_story secret_story: MPEG ADTS, layer III, v1, 128 kbps, 44.1 kHz, Monaural

It turns out this is an audio file, and when I use mplayer to play the file, it turns out to be a kid’s story, and a cute one at that. What about the file called librsave.tgz?

$ file librsave.tgz librsave.tgz: gzip compressed data, from Unix, last modified: Sat Nov 24 07:36:58 2012

To find out more about the file command, type “man file” at the command prompt. As you might have come to expect, most commands do a lot more than it appears on the surface, so finding out more by checking the manual pages is a good idea.

Seek and Ye Shall Find

One of the most useful commands in your arsenal is the find command. This powerhouse doesn’t get anywhere near the credit it deserves. Generally speaking find is used to list files and redirect (or pipe) that output to do some simple reporting or backups. There it ends. If anything, this should only be the beginning. As versatile as find is, you should take some time to get to know it. Let me give you a whirlwind tour of this awesome command. Let’s start with the basics.

find starting_dir [options]

One of those options is “-print” which only makes sense if we want to see any kind of output from this command. We could easily get a listing of every file on the system by starting at the top and recursively listing the disk.

find / -print

While that might be interesting and you might want to redirect that to a file for future reference, it is only so useful. It makes more sense to be searching for something. For instance, let’s look for all the jpeg type image files sitting on our disk. Since we know that these images end in a “.jpg” extension, we can use that to search.

find / -name "*.jpg" -print

Depending on the power of your system, this can take a while and you are likely to get a lot of “permission denied” messages (particularly as you traverse a directory called /proc). If you are running this as a user other than root, you will likely get a substantial number of “permission denied” messages. At this point, the usefulness of find should be starting to become apparent since a lot of images stashed away in various parts of the disk can certainly add up as far as disk space is concerned. Try it with a “.avi” or “.mpg” extension to look for video clips (which can be very large).

If what you are trying to do is locate old files or particularly large files, then try this example. Let’s look for anything that has not been modified (this is the -mtime parameter) or accessed (the -atime parameter) in the last twelve months. The “-o” flag is the “or” in this equation.

# find /data1/Marcel -size +1024 \ \( -mtime +365 -o -atime +365 \) -ls

I’m introducing a few techniques here that are worth noting. The backslashes in front of the round brackets are escape characters, there to make sure our shell does not interpret them in ways we do not want it to, in this case, the open and close parentheses on the second line. The first line also has a backslash at the end. This is to indicate a line break, as the whole command will not fit neatly on one line of the page. Were you to type it exactly as shown without any backslashes, it would not work; however, the backslashes in line two are essential. The above command also searches for files that are greater than 500KB in size. That is what the “-size +1024‘”, means, since the “1024” refers to 512-byte blocks. The “-ls” at the end of the command tells the system to do a long listing of any files it finds that fit my search criteria.

In the last article in this series, I talked about setuid and setgid files. Keeping an eye on where these files are and determining whether they belong there is an important aspect of maintaining security on your system. Here’s a command that will examine the permissions on your files (the -perm option) and report back on what it finds.

find / -type f \( -perm -4000 -o -perm -2000 \) -ls

You may want to redirect this output to a file which you can later peruse and decide on what course of action to take. Now, let’s look at another find example to help you uncover what types of files we are looking at. Remember the Linux “file” command a few paragraphs back? Looking at individual files will tell you what they are, whether they are executables, text files, movie clips, and so on. You can also look at multiple files simultaneously.

$ file $HOME/*

code.layout: ASCII text cron.txt: data dainbox: International language text dainbox.gz: gzip compressed data, deflated, original filename, last modified: Sat Oct 7 13:21:14 2000, os: Unix definition.htm: HTML document text gatekeeper.1: troff or preprocessor input text gatekeeper.man: English text gatekeeper.pl: perl commands text hilarious.mpg: MPEG video stream data

So let’s get file and find working together for some real discovery action. The next step is for me to modify the find command by adding a “-exec” clause so that I can get the file command’s output on what find locates.

# find /data1/Marcel -size +1024 \

\( -mtime +365 -o -atime +365 \) -ls -exec file {} \;

The open and close braces that follow -exec file means that the list of files generated should be passed to whatever command follows the -exec option (in other words, the command we will be executing). The backslash followed by a semicolon at the end is required for the command to be valid. As you can see, find is extremely powerful. Learning to harness that power can make your Linux life much easier and turn you into a superhero. Okay, that last part was pure fantasy.

grepping for Dollars!

The grep command, which I’ll explain in a moment, has lots of definitions for the acronym. My favorite is an oldie; the “global regular expression parser”. Say that five times real fast. There are others, like “global regular expression and print” and “generalized regular expression processing”. Don’t be surprised if you hear it called the “gobble research exercise program” instead of what I called it. Basically, grep’s purpose in life is to make it easy for you to find strings in text files. This is the basic format.

grep pattern file(s)

As an example, let’s say I want to find out whether I have a user named “natika” in my /etc/passwd file; the trouble is that I have 500 lines in the file.

[root@testsys /root]# grep natika /etc/passwd natika:x:504:504:Natika the Cat:/home/natika:/bin/bash

Sometimes you just want to know whether a particular chunk of text exists in a file, but you don’t know which file specifically. Using the “-l” option with grep lets you list filenames only, rather than lines (grep’s default behavior). In the next example, I am going to look for Natika’s name in my email folders. Since I don’t know whether Natika is capitalized in the mail folders, we’ll introduce another useful flag to grep, the “-i” flag. It tells the command to ignore case.

[root@testsys Mail]# grep -i -l natika * Baroque music Linux Stuff Personal stuff Silliness sent-mail

As you can see, the lines with the word (or name) Natika, are not displayed, only the files. Here’s another great use for grep. Every once in a while, you will want to scan for a process. The reason might be to locate a misbehaving terminal or to find out what a specific login is doing. Since grep can filter out patterns in your files or your output, it is a useful tool. Rather than trying to scan through 800 lines on your screen for one command, let grep narrow down the search for you. When grep finds the target text, it displays that line on your screen.

[root@testsys /root]# ps ax | grep apache

Notice the second last line which shows the grep command itself in the process list. We’ll use that line as the launch point to one last example with grep. If you want to scan for strings other than the one specified, use the “-v” option. Using this, it would be a breeze to list all processes currently running on the system but ignoring any that have a reference to ‘grep‘ or, as in the case below, to ‘root‘.

ps aux | grep –v root

The “-v” option means “anything but” the string I specify. In the above case, I’m looking for processes run by non-root users. And speaking of processes, this is where I leave you today, with a little teaser about the next article in this series. Yes, we’re going to explore processes which essentially means all the things that are running on your system; the programs you see and those you don’t. If you wish to comment, please do so here on Google Plus or here on Facebook. Remember that you can also follow the action on CookingWithLinux.com where it’s all Linux, all the time; except for the occasional wine review. Also, make sure you sign up for the mailing list over here so that you’re always on top of what you want to be on top of. So to speak. Until next time . . .

A votre santé! Bon appétit!